Lousy forest management. Pitiless climate change. Increasing urban congestion. Savage droughts, intense storms and relentless overdevelopment, more and more people (like this very columnist) hoping/wishing to escape the madding crowds and build a gentle oasis out in the woods, a place where the dog can run free and the kid can play with the chickens and everyone can roam around without fear of stepping on a heroin needle or nervously checking the car every morning for a smashed window or a $250 parking ticket.

This much we know: A large part of what fueled the ferocious wine country fires, the deadliest and most destructive in state history? The factors that made them so supremely dangerous and unstoppable? A modern, rather unprecedented combination of the ingredients above, and even a few more.

Which is to say: Not only are we little prepared for what’s happening to the planet, for how she is fast devolving, overheating, freezing, burning, flooding and flicking us away like well-meaning, but severely ignorant, irritants, we are making it all much worse.

The tragedy of the wine country fires begets a strange mix of claims, blames and shames: The underfunded U.S. Forest Service doesn’t manage woodlands well. There are far too few controlled burns, minimal clearing of dead tinder, erratic logging practices, the active disallowing of Mother Nature to burn and clear as she, quite naturally, is wont to do.

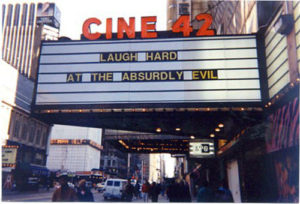

And with climate change, wildfire season has become longer, and more destructive, than ever. From Seattle to Oregon, Los Angeles to SF, Denver to Boise to more than a million charred acres in Montana, the wildfires are incessant and many U.S. cities are increasingly choked in toxic smoke. It’s so bad, and so frequent, a new new term hath been born to demarcate the regions most regularly affected: behold, the ” Smoke Belt”.

This combines with increasing millions of Americans choosing to live near dry, densely wooded areas – a dangerous trend fueled by reckless developers and wayward suburban planning and, yes, the housing crisis, it all points to one dire outcome: more potential destruction, greater loss of life and livelihood, increased tragedy of our own indelible creation. As the New Republic points out:

The U.S. Forest Service expects population growth in wildfire-prone areas to continue. It estimates that there are approximately 45 million homes in the so-called “Wildland-Urban Interface”—the technical term for those in particularly vulnerable areas—and that the number will rise another 40 percent by 2030.

But of course, it’s not just California, or even the west. It’s happening all over the world. As of this writing, 40 people have died in savage wildfires currently ravaging Spain and Portugal, the flames fanned by Hurricane Ophelia and made far worse by extremely dry summer conditions wrought, in large part, of climate change. Meanwhile, more than 1,200 people died and 41 million were displacedby the worst flooding in years in India, Bangladesh and Nepal, the annual monsoons far more deadly than in times past. And you thought Houston was horrifying.

The question gets louder by the season: How are we to adjust to what, by all accounts, appears to be a convulsed, fast-dying world? And can we possibly do it quickly enough?

More specifically, should millions of people really be building houses in wildfire-prone areas? On the flood-prone coasts? In feral hurricane zones? If not there, where should we build? Cities are crammed and traffic is a bitch and once the Yellowstone Supervolcano Earthquake Swarm really kicks into gear, it’s all moot anyway.

Where to find respite, calm, a slice of peace amidst the human firestorm? Did you know 10 of California’s worst wildfires have all occurred in the last 30 years? Did you know the worst, as they say, is yet to come? Personally, I’ve been aching for a slice of land up in the Napa/Healdsburg region, upon which to build a little modern getaway cabin, for what feels like years, saving and searching, planning and devising (I’m not, as they say, swimming in tech bro money). The wine country fires throw the dream right back at me, tragedy-tinged and deeply wary. Are you sure?

But it’s not really a question of money – at least, not for most of those affected. Of course the wine country will rebuild. The majority of those who lost homes and businesses in the Napa area, particularly the wealthier wine companies, have robust insurance policies and plenty of cash to fall back on (not true, of course, of the countless immigrant laborers and hospitality workers of the area – their fate, like most lower-income labor anywhere in the world, is far more uncertain).

The region will resurge, the trees will sprout anew, the tourists will come back and the cycle will, barring massive change to climate policy, start all over again. But should it? How smart is it to build a home on the side of an active volcano? How surprised should you be when it gets eaten by lava? Or is that “just life” these days? Is imminent, hreatbreaking catastrophe just the new normal?

It all begets the larger, and perhaps more distressing, question: Is there anywhere you can really go to be safe from mother nature’s backlash, from the hell we have wreaked upon her? Is there any such thing as a “perfect” haven anymore? The coasts, science tells us, will soon be at least partially underwater, the devastating droughts of world are already getting far more frequent, the rains more engulfing, the hurricanes, tornadoes and superstorms more destructive. Climate change is upon us, and lo, it cares about your well-being as much as Trump cares about #metoo.

To be sure, no place in the world is entirely safe from potential calamity. Human existence is, by definition, crammed with risk, be you hit by a bus on the city sidewalk, eaten alive by flesh-eating bacteria or tossed like confetti by a tornado. We’re all going down, eventually. Life, for the everyday fatalist, is just a matter of (quiet, desperate) mitigation. But really, who wants to live like that?