Every summer of my existence, I’ve spent at least a week or two – if not major portions of my childhood – up at a postcard-perfect family getaway cabin in northernmost Idaho, on a stunning lake called Pend Oreille, mere minutes from a scrappy little Western town called Sandpoint (surviving though “sheer grit and perseverance,” according to the NYT). Magical barely begins to cover it.

And every summer for fast approaching five decades, it’s been gloriously the same: mid-July through late August, it’s a near-perfect bouquet of 90-degree days and crystalline, star-soaked nights, the air itself becoming imbued with a soft, healing quality and all of it interrupted by the occasional feral, window-rattling summer thunderstorm to remind you of nature’s omnipotence, right up until Labor Day, when faint hints of fall begin to paint the breeze.

In short, it’s just sort of stupidly idyllic, a spectacular way to clear the mind and the lungs at one of the more pristine, unpretentious places on the planet, as yet despoiled by mega-developments or decimated by the roiling national economy.

But this year, for the first time since I can remember – and maybe for the first time in a century or more – something changed.

This year, there were wildfires.

Not the typical wildfires, mind you. Not the normal smattering of (relatively) easily controlled seasonal blazes that nature herself always ignites to help purge and clear; I mean all the massive, drought-amplified, state-engulfing wildfires you’ve been hearing about all season long – nearly all of them larger, earlier and more frequent than any time in modern history, ranging from a few thousand acres to the largest in the country, the Soda fire, currently engulfing upwards of 265,000 acres in southern Idaho, which joins with all the other Pacific Northwest fires burning throughout Washington, Oregon and Montana. And here you thought just California was ablaze.

Do you know about Alaska? Nearly five million acres have burned throughout that unusually hot, dry state this year, which is a record, which is something like the size of Connecticut (combined), which is more staggering than your heart can process. Go ahead, try it. And then add in Canada’s staggering wildfires, and you hit upwards of 11 million scorched acres – that’s 17,000 square miles, and still going strong. That’s terrifying.

More firemen, more money spent, more resources dedicated to fighting this years’ fires than any year previous. And it’s far from over.

The scariest part? Fire season, historically speaking, doesn’t even begin until September. Did you know 2015 is already officially the hottest year ever recorded on Earth? Did you know Alaska recorded its hottest month ever, in 91 years of record keeping, in May? The worst – as nearly every scientist, climatologist, environmentalist in the world is all too sick of saying these days – is yet to come.

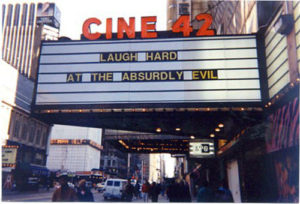

How dire do you want it? What’s it going to take? As Eric Holthaus over at Slate recently put it WRT the huge and immediate changes needed right now from the UN and various self-serving, combative, greedy world leaders to combat this downward spiral: Where is everyone?

(Here’s your must-read of the month: The New Yorker profile of the amazing Christiana Figueres, head of the UN’s Framework Convention on Climate Change – the U.N.F.C.C.C. – and just what she’s up against in trying to rally member nations to make real changes, right now).

This year, my summer visit to Idaho was swallowed, most days, in a thick, gauzy haze. It was as though the sky was overlaid with a bleakest of Instagram filters; the smoke was often so dense, it blocked the blue light spectrum entirely, washing everything in a pale, flat yellow, a creepy, apocalyptic tint that contrasted well with the redness in your eyes and the gray dryness of your throat.

Here’s the thing: It wasn’t just weird. It’s not just “an unusually hot and dry season.” You can feel it in your very cells: this is all part of a increasingly vicious, mean-ass vortex of accelerating evidence that the planet and all its animals – of which we are merely one – are under a potentially fatal stress like no other time in modern history.

Put another way: It’s not merely about preparing for rough weather. It’s not about stocking up on extra water, flashlight batteries, a solar iPhone charger. Climate change doesn’t merely mean life is going to get much more difficult, much more quickly than most people – particularly the rich and oligarchic – can possibly imagine. It means it’s going to get much more disquieting.

The very tone and timbre of life is changing. The air is shifting, the light. As ecosystems collapse, as animals either hatch in bizarre megaswarms or vanish completely, as forests whither and thin out, the planet’s increasingly palpable failure to hold itself in some kind of equilibrium is going to creep into your very spine, shake your dreams. Don’t believe it? Just wait.

Winter will soon come and finally put out all the fires, to be replaced by (if all predictions are to be believed), savage El Niño flooding, pounding the bone-dry, unprepared ground, which in turn will be replaced by yet another scorching summer. Did you know we’re pumping more C02 into the atmosphere than ever before in history? Did you know we’ve wiped out half the planet’s wildlife in just the past 40 years?

Up in Idaho, when the smoke was so thick it turned the sky a pallid urine color, I noticed something else: the birds.

They stopped chirping. The air often fell dead still. No bees, no bugs, no osprey, no eagles; the smoke appeared to choke off all normal, life-affirming activity. I heard reports of herds of parched, exhausted, soot-covered elk and deer crossing local highways, seeking water and relief from the fire. That same afternoon, I noticed a huge swarms of dead flies – not the usual lake gnats, the no-see-ums and such – but large, black flies, by the tens of thousands – covering the surface of lake near our cabin. I skipped my swim.

This is what we have yet to realize: it’s not just about preparing for more severe weather. It’s far more about what’s about to happen to the experience of life itself, how we navigate our terrifically spoiled, entitled daily lives and with what newfound combination of panic and kindness – all amplified, to a rather terrifying degree, by the realization that the more we refuse to change our gluttonous ways, the more nature is going to step in and change them for us.

Read more here:: Everything is on fire and no one cares